ND: I

am a first-generation American, the son of post-World War II immigrants

from Ukraine and grandson of an Orthodox priest. While not a

stereotypical "PK," I essentially grew up in and around a rectory and

took great pleasure in singing with the church choir. After graduating

from the University of Minnesota with a BS in Business in 1994, I took

my first job with St. Mary's Orthodox Cathedral in Minneapolis as their

music director. I received my M.Div. from St. Vladimir's Seminary in

2000, worked as a product manager at Augsburg Fortress Publishers until

2003, graduated from The Catholic University of America with a Ph.D. in

liturgical studies and sacramental theology in 2008 (with a short stint

as marketing manager at the USCCB from 2007-9), and accepted an

appointment as assistant professor of theological studies at Loyola

Marymount University in Los Angeles, where I also direct the Huffington

Ecumenical Institute.

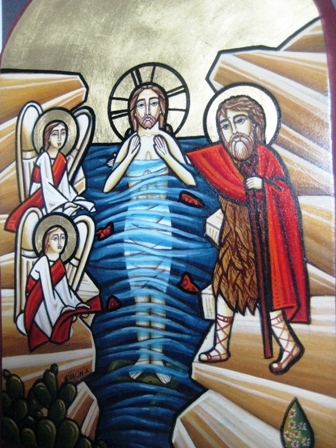

AD: What led you to work in the areas of liturgical theology, and in particular on the question of Theophany and water blessing?

Well,

when I turned 18, after a lifetime of praying in my non-native language

(Ukrainian), I honestly began the process of "faith seeking

understanding." A friend gave me a copy of Alexander Schmemann's book Liturgy and Life

which I eagerly read. I continued to read Schmemann

in my quest to understand liturgy, which I had actively engaged as a

choir director. One motivation was my own need to teach liturgical music

and to demonstrate to singer how music is a servant of the liturgy; the

only way to accomplish this was to learn liturgical structures, history,

and theology. My interest in the Theophany water blessing began in a

seminar on the Holy Spirit I took with my Doktorvater

, Dominic Serra, in

2004. My desire was to unpack the mystery of the so-called "double

epiclesis" of the "Great are You" prayer, and my entrance into the

project became something much more significant and definitive.

AD: Among several outstanding things about your study I found two

especially commendable. First is your ecumenical focus in which you

don't just confine yourself to the Byzantine tradition but also examine

other Eastern traditions as well as Roman Catholic and Anglican

liturgical treatments of Epiphany and blessings. Is there evidence of

Eastern traditions influencing the Western, or vice versa?

ND:

There is no doubt that the Anglican water blessing draws

upon elements of the Byzantine and perhaps Armenian traditions, which

are then synthesized in a beautiful blend of Theophany and Western

Epiphany themes of "greeting," an anticipation (as it were) of the

second coming. In other words, it's as if the Baptism of Jesus at the

Jordan has a powerful eschatological flavor in anticipating his

revelation as Lord and God at the end of days. More work needs to be

done in this area. A Hungarian scholar is about to publish a critical

edition of the blessing of waters in Latin which appears to draw heavily

upon Greek euchological sources, so there is some evidence of East

influencing West, in both medieval and contemporary sources.

AD: You draw on a wonderful array of people in your

work, including some very prominent names in Roman Catholic, Byzantine

Catholic, Anglican, and Orthodox circles, inter alia. Is it possible

today (in the shadow of

Baumstark as it were) to do liturgical theology

using anything other than such a comparative method?

ND: Employing the comparative method is essential for writing

liturgical history, and I humbly consider myself to be an adherent of

the Baumstark-Mateos-Taft school of comparative liturgy, with special

thanks to Mark Morozowich (Dean of the School of Theology and Religious

Studies at The Catholic University of America), who carefully taught me

the method. My work is also one of sacramental theology, and here, I

employed Monsignor Kevin Irwin's method of Context and Text, an

enormously valuable method for gleaning liturgical theology. Liturgical

Studies is gradually becoming interdisciplinary, and I think we will see

these methods evolve, develop, and grow, especially now, since the

liturgical movement and its fruits are increasingly scrutinized and

criticized in Catholic and Orthodox circles.

AD: The second thing I greatly cheered was your

chapter "Pastoral Considerations." Some liturgical scholars see their

task as largely confined to narrating history, which is said to be

"instructive but not normative." But you don't confine yourself only to

history: you put forward some very interesting practical-pastoral

proposals. Tell us what led you to do that.

ND:

The task of liturgical history is to inform, and not

reform. Two of the best liturgical historians of our time, Taft and

Maxwell Johnson, have been quoted accordingly. In the case of the

blessing of waters, we are speaking of a living tradition, a real

practice in which people participate. In the case of the blessing of

waters, history can inform contemporary practice, especially since the

Theophany feast occurs right after the New Year, when most people have

returned to work (even academics!). This feast is beloved to Eastern

Christians: why not maximize and optimize participation? The models I

propose are really not attempts to reform, but instead a fine-tuning--pastoral adjustments that are designed to provide people with greater

access to the blessings of the feast. My proposals concerning Catholic

and Reformed churches draw upon the Roman tradition of adaptation and

are offered in the spirit of ecumenical gift-exchange.

AD: The current Ecumenical Patriarch, as I'm sure

you're aware, is often called the

"green patriarch" for his concern

about ecological issues. Do you see the theology of water blessing as

connected to current concerns for the environment?

ND:

Yes, absolutely. The blessing of waters reveals all of

creation as holy, and water, symbolized by the Jordan, is the locus for

salvation. All of creation participates in the praise of God as holy, of

Christ as Lord, in this feast. Water is God's preferred instrument of

salvation, a gift to humanity of restoration to the community of the

Trinity. The ecumenical patriarch often referred to the blessing of

waters in his many speeches and homilies as a demonstration of

Orthodoxy's prioritization of ecological stewardship. I contend in this

study that the blessing of waters essentially demands that the Church

contribute to the global task of developing a new ethos of water; we

have much to contribute from our lived tradition.

AD: Your introduction notes that there is a question,

in the Theophany prayers, as to the identity of the one to whom the

prayers are addressed. You then note the possibility that perhaps not

all prayers are addressed to the Father through Christ, but to Christ

directly, and this may pose a challenge to traditional Trinitarian

theology from John of Damascus onward and its resolute insistence on

"protecting" the "monarchia" of the Father. Say a bit more about this if

you would, including some of the ecumenical implications.

ND:

The euchology and hymnography of the blessing of waters

is distinctly Christological. The texts, together with the ritual action

of submerging the cross into the waters, tell the story. The Church

invokes her head, Christ, to sanctify the waters by entering them; the

Spirit bears witness to this entrance. Comparative liturgy not only

confirms, but strengthens this thesis, as the Christological trajectory

of the rite is even more prevalent in the Oriental tradition. I contend

that the blessing of waters should be consulted as a source

in Trinitarian theology, because the rite clearly contradicts the

longstanding and fatuous claim that all prayer must be addressed to the

Father. My invitation to theologians is to consider the ecclesiological

framework of prayer when the Church as the body calls upon the head,

Christ, to act. Some might say that this framework only concerns the

economy of the Trinity, and that the monarchy of the Father as the

source of divinity for the three persons of the Trinity is not

threatened by the framework. My hope is that this framework might be

useful in an ecumenical context to advance the notion that the filioque clause can no longer be cited as a Church-dividing issue, and that

theologians might recognize the dynamics of Trinitarian prayer and

activity in the Theophany blessing of waters as a demonstration of

fluidity in the divine economy.

AD: Why is it that Theophany ("Jordan") in the East

retains, it seems to me (at least among the East-Slavs, with whom I am

most familiar), such a place of popularity in the yearly liturgical

cycle? Is there something unique about this blessing that people, even

without perhaps articulating the whole theology of the feast, grasp in

their piety?

ND:

Among many people of the Byzantine tradition,

the Theophany feast carries a strong popular parallel to Christmas, with

carols, and traditional foods, not to mention a similar liturgical

structure. There are many potential reasons for the popularity of the

Theophany feast, but if I were asked to focus on one, it's the simple

human need for water. Somtimes, in a hyperacademic drive to unveil an

original theological idea, we overanalyze texts and contexts and

overlook the obvious. On Theophany, the people take the blessed water

home and use it throughout the year. The churches are packed on similar

occasions when food and drink are blessed: on Transfiguration, we bless

fruits, and take them home, and of course on Pascha, pastors have to

schedule multiple basket blessings. In the moment, we tend to complain

about the apparently trite attitude of the people, who don't recognize

receiving the Eucharist as the authentic meaning of feast. But it's

erroneous to dismiss the people's recognition that the sacred is welcome

in their domiciles. Whatever we bring to Church, whether it's water for

the Theophany feast, bread and wine for communion, eggs and other

savory foods for Pascha baskets, fruit for Transfiguration, or flowers

for Dormition, the act of bringing such items to Church is authentic

offering and thanksgiving, a recognition that these domestic foods and

elements are holy gifts from God freely given to us for our

enjoyment. These traditions so dear to the people also serve as stark

reminders that the domestic setting, the family (small or extended), is

sacred, and that there is no real separation between the holy space of

the Church and that of the home. The time has arrived for pastors to

recognize these instances as opportunities to build upon what people

themselves already recognize, that God is always with us, everywhere we

go, and especially in the gifts of creation He has entrusted to our

stewardship. These examples represent strong liturgical episodes (to

paraphrase Monsignor Kevin Irwin), and not only should we be thankful

for them, but we should also recognize the divine philanthropy

they convey to us.

AD: Sum up for us what you hope the

The Blessing of Waters and Epiphany: The Eastern Liturgical Tradition accomplishes.

ND: I hope the book will be informative for broad audiences.

There used to be a saying about Eastern Christianity in North America that it's a well-kept secret. Scholarship on the Eastern Church and her

traditions has begun the process of demythologizing Eastern

Christianity. Today, almost everyone knows about icons, and among

theologians, terms such as hesychasm and theosis are well-known. That

said, there are many other Eastern secrets that could be unveiled and

have the capacity to tell a more comprehensive narrative story that

complements what most people already know about Eastern Christianity. My

hope is that this book will provide insights into Eastern Christian

liturgical theology that demonstrate its diversity within the tradition,

its theological fluidity, and its incredibly beautiful Christology,

still experienced in a lived tradition.

AD: Finally, tell us what projects you are working on now.

ND: I'm

writing a book on Chrismation for Western Christians. The premise of my

book is that within the Byzantine tradition, Chrismation, like its

Western sibling (Confirmation), is also a mystery in search of a

theology. My book (under contract with Liturgical Press) endeavors to

unpack the liturgical theology of Chrismation in dialogue with the

Catholic and Reformed traditions, to take a step towards retrieving the

theology of Chrismation. I'm also steadily working on an architecture

project profiling select Orthodox parishes in America. My project

endeavors to recast the theology of architecture as multifaceted, and no

longer an instance of form following function. My thesis contends that

contemporary architecture conveys the narrative story of ecclesial

communities with the local Church's mission now the primary shaper of

architectural form.

edition.

edition.